ANALYSIS: The rise and fall of the Homer G. Phillips Hospital

- Jun 11, 2025

- 14 min read

An all-black hospital sounds like science fiction to many even today. That’s why it comes as such a surprise that an all-black hospital flourished from 1937 to 1979 in St. Louis, Missouri.

During much of that era, blacks were not allowed admittance to white hospitals, and there were few and temporary black hospitals.

As of 2023, there is only one Black-owned hospital in the United States: Howard University Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Historically, there were more Black-owned hospitals, particularly during the era of segregation. However, many of these hospitals closed due to financial difficulties or integration, and thus competition with major brands.

While it's difficult to provide an exhaustive list of all historically Black hospitals founded since 1920 due to the vast number of institutions that have existed and some closures over time, here are some notable examples based on the provided search results:

Hospitals founded in the 1920s:

L. Richardson Memorial Hospital in Greensboro, NC (founded 1923, now closed).

Riverside General Hospital in Houston, TX (founded 1925).

Later 20th-century institutions:

Southwest Detroit Hospital in Detroit, MI (founded 1974, now closed).

There were numerous other Black hospitals established during the "Black hospital movement" between 1920 and 1945, created to provide healthcare access and professional opportunities for Black Americans during a time of widespread segregation.

Historically Black Hospitals Mentioned (regardless of founding date):

Howard University Hospital in Washington, DC (founded 1862).

Richmond (VA) Community Hospital (founded 1902).

Nashville General Hospital at Meharry (formerly George W. Hubbard Hospital) in Nashville, TN (founded 1910).

Norfolk (VA) Community Hospital (founded 1915, closed 1998).

Newport News (VA) General Hospital (founded 1915, now closed).

Provident Hospital in Chicago, IL (founded 1891).

Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School in Philadelphia, PA (founded 1895, merged in 1948).

Mercy Hospital in Philadelphia, PA (founded 1907, merged in 1948).

Mercy-Douglass Hospital in Philadelphia, PA (formed by the merger of Frederick Douglass Memorial and Mercy Hospital in 1948, closed in 1973).

Saint Agnes Hospital in Raleigh, NC (established 1886, closed 1961).

Lincoln Hospital in Durham, NC (founded 1901).

Freedmen's Hospital (now Howard University Hospital) in Washington, DC (established 1862).

Taborian Hospital in Mound Bayou, Mississippi (established 1942, closed 1983).

Harlem Hospital Center in New York City.

Homer G. Phillips Hospital.

The medical scene was bleak, foreign, and hostile for blacks during much of the 1900s, whether north or south, east or west.

Therefore, what were the unique dynamics that converged for the concept, construction, operation, and maintenance of a black hospital?

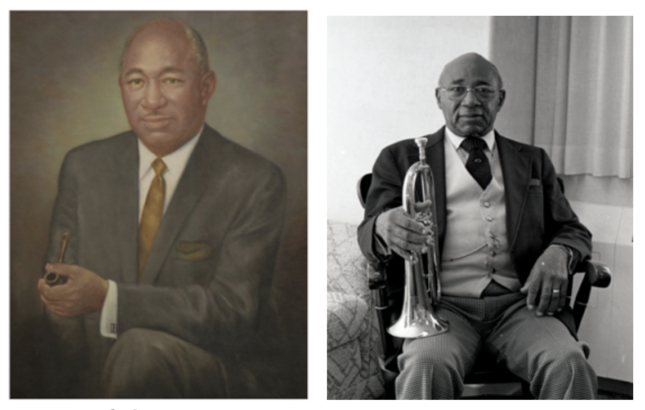

Homer G. Phillips

Phillips was a prominent black lawyer who spearheaded the movement for a black hospital. He garnered the black elite, powerful white businessmen, politicians, and others to support the hospital.

Because of infighting, it took ten years for construction to start on the hospital.

The architect

Architect Albert A. Osburg was the staff architect for the city of St. Louis. He had drawn the plans for many other outstanding buildings. So, he was the logical choice for this hospital also.

Hospital funding

St Louis passed an $89 million bond issue, with $1 million earmarked for a hospital that would care for Black patients. A dispute soon raged over whether the hospital should be free-standing or an adjunct to the white city hospital. Many black leaders pushed for a separate building. Although at first, Phillips asked for an adjoining building, he later changed his mind and asked for a separate structure.

It was clear, however, from the beginning to the end, that the white establishment adamantly opposed adjoining hospitals.

Homer G. Phillips Hospital was funded by a combination of a city bond issue and funding from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the New Deal by Franklin D. Roosevelt, mainly at the behest of his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt. Initially, a $1 million bond issue in 1923 was allocated for the hospital, along with an additional $200,000 from the city government. However, due to indecision on the construction plan, these funds were not immediately used. The WPA then provided the remaining funding needed to build the hospital. Additionally, the Roosevelt administration allocated extra funding for the hospital as part of their expansion of healthcare to underserved areas.

Political infighting postponed the construction until 1932, and it was open to the public in 1937. The 25 ensuing years demonstrated how the hospital flourished and benefited untold thousands.

A thriving hospital

During the first year alone, more than 100,000 patients were given top-quality healthcare. Indeed, the level of care remained above standard for the whole of existence.

During the heyday of the hospital in the 1940s, it had 685 patient beds.

In fact, it was not closed because of poor performance but because of naked hatred and jealousy in the face of many positive proofs that the hospital was vastly superior to the norm.

Significance:

Homer G. Phillips Hospital became a major training center for Black doctors and nurses, playing a significant role in shaping the medical landscape of the era.

Address 2601-15 Whittier St., St Louis, Mo.

Medical schools of the day

In the 1930s, two prominent medical schools at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were Meharry Medical College and Howard University College of Medicine. These schools played a significant role in educating African American physicians, particularly after the Flexner Report led to the closure of many other medical schools serving the Black community.

Flexner Report

Written by Abraham Flexner and Herman Gates Weiskotten.

Medical authorities say in retrospect that the

The Flexner Report was both accurate and biased, depending on how one interprets its findings and recommendations. While it accurately described the state of medical education in the early 20th century, highlighting shortcomings in many schools, its recommendations were influenced by Flexner's own biases, particularly against alternative medicine and in favor of a specific model of medical education.

This led to the quick closure of many black medical colleges and universities, greatly limiting opportunities for blacks to become doctors.

Two black universities remained: Howard and Meharry College.

The closure of many Black medical colleges following the 1910 Flexner Report was extremely detrimental to the education, healthcare, and socioeconomic advancement of African Americans in the United States. Here’s a breakdown of its impact:

🔍 Background: What Was the Flexner Report?

The Flexner Report, commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation and written by Abraham Flexner, aimed to reform U.S. and Canadian medical education. It criticized low-quality, for-profit schools and advocated for a science-based, university-affiliated model—aligned with Johns Hopkins.

Consequences

Thousands of potential Black physicians were denied opportunities.

It narrowed the pipeline of Black professionals in a time when segregation barred them from white institutions.

2.

Health Disparities Widened

This exacerbated long-term racial health disparities, many of which persist today.

3.

Institutional Setback for HBCU

Loss of medical schools weakened the academic and financial foundations of HBCUs.

It stunted their ability to contribute to research and professional training for decades.

4.

Reinforcement of Segregation and Racism

The report reflected and reinforced racist ideas that Black Americans were suited only for limited roles.

Flexner’s own writing suggests he believed Black physicians should serve only Black patients and in subservient medical roles.

Long-Term Effects

Even by 1960, Black people made up only 2.8% of U.S. physicians.

Many contemporary efforts to improve diversity in medicine are still trying to counter the damage done by the closures.

Schools that produced black nurses

In the 1930s, several nursing schools played a crucial role in educating Black nurses, often facing significant challenges due to racial discrimination. Key institutions included:

Freedmen's Hospital School of Nursing (later Howard University School of Nursing)

.

Established to train Black nurses, particularly for the care of freed slaves in Washington D.C.,

A cadre of nursing schools framed a backbone of support for the hospital

.

One of the earliest nursing schools for Black women, founded in 1898, and highly regarded by the 1930s, according to the National Library of Medicine.

Harlem Hospital School of Nursing:

.

Established in 1923 to address the lack of nursing schools in New York that accepted Black women, according to Wikipedia.

Blue Ridge Hospital School of Nursing:

.

The only nursing school for African American students in Appalachia from 1925-1930, it closed due to the Great Depression, according to Appalachian State University.

Provident Hospital Training School

Established in 1895, according to the University of Illinois Chicago.

Tuskegee School of Nurse-Midwifery:

.

Located on the campus of the Tuskegee Institute, this school focused on training Black nurse-midwives, according to ScienceDirect.com.

Cleveland City Hospital (first in the area to admit Black students), Medical College of Virginia (MCV, had a segregated school for Black nurses), and Fannie S. Burley School in Charlottesville, Virginia (had a Licensed Practical Nurses Program).

Blunt forces smashed the hammer down

An armed police force closed the doors of the Homer G. Phillips Hospital on August 17, 1979. The closure sparked protests and outrage within the Black community, as it dealt a devastating blow to vital resources for black patients who then had no medical care.

The closure of Homer G. Phillips Hospital was driven by Mayor Jim Conway and supported by the City's Board of Aldermen. The black political community and some white elected officials vehemently opposed this decision, according to the St. Louis American. Schoemehl, a 28th Ward alderman at the time, also played a role in the closure.

The glory days

In the first year of the Homer G. Phillips Hospital, more than 100,000 patients were treated.

Here are a few of the surgeons who became famous

Ezelle Sanford III

Dr. Howard Phillip Venable

Dr William Sinkler

After graduation, Dr. Sinkler moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where he served as a junior intern, assistant resident in surgery, and resident surgeon. In January of 1938, Dr. Sinkler was appointed as consultant in chest surgery at Koch Hospital, the first member of his racial group to be honored. In 1941, Dr. Sinkler was made medical director of the Homer G. Phillips Hospital, where he was an outstanding hospital administrator, distinguished surgeon, and Assistant Professor of Surgery in the Medical School of Washington University.

Doctors Kinkler and Vaughn were invited to perform a surgery under the eyes of a panel of white doctors in Monroe.

Unequal treatment and facilities prevailed outside of the Phillips Hospital, so that the black doctors were asked to don their scrubs, caps, and masks in the janitor’s closets.

Hysterectomies are often performed in about two hours or more, but Dr. Kinkler was performing this procedure at such a breakneck speed that one of his critics was compelled to shout out in there amazement, “look at that nigger go.” The procedure took 20 minutes. All were astounded at the accuracy, precision, and speed. There were no ill effects.

Pediatrician, Mary Ann (Tuggle) Tillman, MD.

She was the director of the nursery of the Homer G. Phillips Hospital.

Dr. Donald M. Suggs DDS

Instead of grouping all the babies together, the head nurse ordered the babies to be placed in individual basket-nets for babies. This one adjustment dropped the mortality rates drastically.

Doctors and patients alike felt like they had died and gone to hospital heaven.

A “great white doctor” disagreed with black doctors about the diagnosis of a patient with a bloated stomach. The hospital doctors said the fluid lay just under the skin and would squirt out when the skin was punctured. The white doctor confidently disagreed, asserting that the fluid was contained within an organ that must be punctured to drain the fluid.

However, as soon as the white doctor punctured the stomach skin with his scalpel, the fluid squirted out, striking the ceiling lights eight feet above the surgical table.

Immediately, raucous laughter erupted, and the white doctor's face flushed bright red. Silence eventually engulfed the group, and the doctor slunk out of the room, dejected and sullen.

Initially, great white doctors were appointed as department heads. Little by little, others replaced them. In time, a black doctor was appointed as head of the hospital.

Dr. Helen Elizabeth Nash

The first Black doctor to serve as head of Homer G. Phillips Hospital was Dr. Helen Elizabeth Nash. She served in that capacity and also as president of the St. Louis County Medical Society. She is recognized for breaking down racial barriers and making significant contributions to the hospital and the medical community.

This pediatrician had something to prove. Nash was determined to become not just a doctor but the doctor of note. And she attained that goal and then some.

Dr. Nash broke through gender and racial barriers during her career. After graduating from Spelman College in 1941, she was one of the very few women attending Meharry Medical College in 1945. Upon completion of her pediatric residency at Homer G. Phillips Hospital in 1949, Dr. Nash was one of only four African-American physicians (and the only woman among them) invited to join the Washington University School of Medicine faculty, as well as the first African-American asked to join the St. Louis Children’s Hospital staff.

An energetic, ambitious, and highly committed physician, Dr. Nash also started her private practice in 1949, while remaining on staff at Homer G. Phillips Hospital, serving as pediatric supervisor and associate director of pediatrics from 1950 to 1964. She was president of Children’s Hospital attending staff from 1977 to 1979. Dr. Nash retired from private practice and her faculty position in 1993. She then served as dean of minority affairs for Washington University School of Medicine from 1994 to 1996.

Engine of change

Word rapidly spread about the Phillips Hospital, and student nurses and doctors came from the South as indigents, but eager to learn and willing to work hard. Soon, they entered the burgeoning middle class.

Nurses became deeply immersed in the community to become well-rounded. To that end, student nurses participated in all levels of society, clubs, charities, schools, and churches. All this preparation fostered a deep sense of empathy for patients, though all black, but still diverse in endless ways because of their circumstances, persuasions, preoccupations, education, religions, and occupations.

There was a coordinated effort to deck the nurses out with specially designed high-heeled shoes with silk shoestrings, the most comfortable footwear for standing on your feet for long hours without consequences. “This saved our feet. We always had the best, even when they had to fight for it,” said the nurses.

Today, a hysterectomy typically takes about 2 hours, but the actual procedure duration can vary depending on the type of hysterectomy performed and individual patient factors. For example, laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomies might take longer than a traditional abdominal hysterectomy.

It was routine for those skilled surgeons to perform a hysterectomy in 20 minutes with one sponge, scissors dangling on their fingers, always in perfect control of every phase of the procedure.

Nurses were trained to put instruments in order as needed, neatly aligned on a convenient table for surgeons to easily reach them. Nurses were trained to anticipate which instruments doctors would need in advance, so there was no need to ask for an instrument, as is the custom in other operating rooms today.

The records in our medical library were our Bible.

We maintained and periodically updated manuals, which were conveniently stored in our medical library. So when a pressing question arose, we could quickly check the library, find the solution, and save the patient.

Today, hospitals no longer have a medical library. Instead, in this digital age, they hire healthcare managers.

The path to the end

The Phillips Hospital was known for providing training and work to foreign doctors.

Here's how that happened and the impact that resulted:

During the early 1950s, foreign doctors, particularly physicians of color, were often denied training opportunities in other hospitals due to racial prejudice.

Providing opportunities: The Phillips Hospital actively offered training and work to these foreign doctors, easing staff shortages and providing them with opportunities they were otherwise denied.

Consequences:

By 1961, the Phillips Hospital had trained the "largest number of black doctors and nurses in the world".

Diverse staff: The influx of foreign doctors alongside Black American physicians contributed to a diverse and skilled medical staff.

Improved patient care: The presence of a larger and more diverse medical staff improved the quality of care provided to the community, particularly the Black community it primarily served.

Physicians who trained at Homer G. Phillips, including those from other countries, went on to achieve significant medical advancements in various institutions, boosting the hospital's reputation as a center for medical research.

Off stage, critics stewed over conspicuous success.

In summary, the Phillips Hospital's willingness to provide training and work to foreign doctors, at a time when they faced racial discrimination elsewhere, was a significant factor in its success as a training institution and contributed to its legacy as a vital hub for medical education and research.

The striking success, unexpected by some, was a source of great uneasiness for certain ones in power. They frantically searched for a pretext that would allow them to save face while closing down the hospital.

Forces conjured up nefarious government policies, ending in clandestine attacks that forcibly shut down a defenseless hospital.

The permanent closure of Homer G. Phillips Memorial Hospital in St. Louis was primarily due to deficiencies leading to a surrendered license. Specifically, the hospital surrendered its license to Missouri health officials after failing to submit a thorough correction plan for hospital deficiencies. The state had initially suspended the hospital's license. It's worth noting that one commenter on Facebook suggested a "money scandal" was involved, implying financial issues played a role. However, the immediate cause cited in the provided information is the failure to address the identified deficiencies to the satisfaction of the state health officials.

It is important to differentiate this situation from the issues concerning Philips Respironics, a company that produces medical devices such as ventilators and CPAP machines. Philips Respironics faced recalls and legal actions due to problems with foam degradation in their devices, which could cause serious health risks. These are distinct issues from the closure of Homer G. Phillips Memorial Hospital.

It must be remembered that by the time of the closure, the hospital no longer had an all-black clientele. In fact, it had been gradually luring away white patients from the other hospital in town. Herein lies another factor leading to handwringing and irritation by the establishment.

Regardless of the political posturing, the police with angry dogs, the National Guard, and only God knows who else arrived with helicopters circling overhead in unison and manhandled staff and patients to close the hospital down. The ferocity of the attack prompted many staffers to ask, just what kind of response did they expect from the overwhelming force to close the hospital down?

While the sources don't explicitly mention staff and patients being manhandled by police during the 1979 closure, more than a hundred police officers were present to escort patients out of the hospital. This suggests a tense atmosphere.

Context:

Sending over 100 police officers to escort patients from a closing hospital could be seen as an overreach of police authority.

Sure, there were protests, but Blacks committed no violent acts on the day of the closure or at any other time. That’s why community members were appalled by such a strong show of police force at a hospital.

The community struggled for years to reopen the hospital, but it never happened.

The first step was to cut off the switchboard, and then the police came. Senator Gwen Giles and many other people of various ranks were eyewitnesses to the closing of the hospital.

Not even the staff were told in advance. It was closed like a military operation at 5 pm. Helicopters, the National Guard, and police with barking, snarling dogs ( in typical Bull Conner’s fashion) came in unison and closed the building. The hospital was officially closed on August 19, but it was cut off from the people on the 17th.

The community was blindsided by the closing because, in part, the city had just completed a $2 million update of the ER.

In the aftermath of the closing, Vincent C. Schoemehl was a candidate for mayor of St. Louis who promised to reopen the Hospital, but did not deliver on his promise once elected, according to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

A full-service senior home

The Homer G. Phillips Hospital was eventually converted into a full-service senior home by a single individual. The process involved a series of negotiations and development efforts, with Sharon Thomas Robnett ultimately leading the project to repurpose the building.

The repurposing of the hospital into a senior home did not ease the pain for many in the community; it only added salt to the open wound.

Epilogue

This is a lesson, not of colossal failure and mismanagement, but of the ferocious pushback to success, thus producing the cycle of hatred and demolition, and liberalism and accomplishment.

When a ship sails against the wind, it follows a zig-zag course called tacking, also known as beating to windward. This zig-zagging maneuver allows the ship to make headway towards the wind without sailing directly into it, where the sails would stall.

Thus, the restless sea of humanity, fickle and unpredictable, rallies for progress at times and then opposes it.

Any future success that emerges may not be with hospitals, but in another arena. Sadly, once the death nail has been hammered into the coffin of black hospitals, who knows what other enterprise will likewise produce a short-lived triumph?

Striving for a purely human solution requires an unreasoning faith and the maddening determination of an Egyptologist. Occasional, spotted, and short-lived progress is not the ultimate goal.

So, after 25 years, the living dream was over, never to return. No amount of civil agitation, demonstrations and conniving, or scheming, which quickly ensued, restored the hospital.

But the monument of the senior home, singularly, remains a stoic reminder of what had been, and of a brotherhood that would require greater power than what has exerted itself thus far in the plane of human endeavors.